Mobile First: How Banks Are Becoming Crypto Products

Consumer-Grade DeFi: Treasury as Banker

In Western societies, finance operates as a mechanism for social mobilization, thriving only when there is a distinct separation—or even tension—between the state and society. Conversely, in major Eastern nations where the state and society are structurally unified, social mobilization depends on large-scale infrastructure and governance capabilities.

With this context, let’s examine the current landscape: after a decade-long, hasty conclusion to the Ethereum and dApp narrative, DeFi has pivoted toward the mobile Consumer DeFi app race on platforms like the Apple Store.

Unlike exchanges and wallets that quickly launched on major app stores, DeFi—long confined to web interfaces—was slow to adapt. Meanwhile, virtual wallets and digital banks targeted specific markets such as low-income and unbanked populations. DeFi, unable to address credit system challenges, entered the market prematurely.

This ongoing dilemma has even revived discussions about society’s shift from monetary banking back to fiscal monetary systems.

Treasury Reclaims Monetary Authority

The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.

Consumer-grade DeFi, led by solutions like Aave and Morpho integrated within Coinbase, directly targets retail users. To understand why DeFi Apps are now surpassing DeFi dApps, we need to revisit the origins of modern money issuance.

Gold and silver were never inherently money. As trade expanded, commodities emerged as universal equivalents, and gold and silver, due to their intrinsic properties, gained broad acceptance.

Before the Industrial Revolution, regardless of political structure or development stage, metal coinage dominated, with treasuries managing the monetary system.

The central bank–commercial bank model is a relatively recent phenomenon. In early developed economies, central banks were created as a last resort to resolve banking crises—this includes the familiar example of the Federal Reserve.

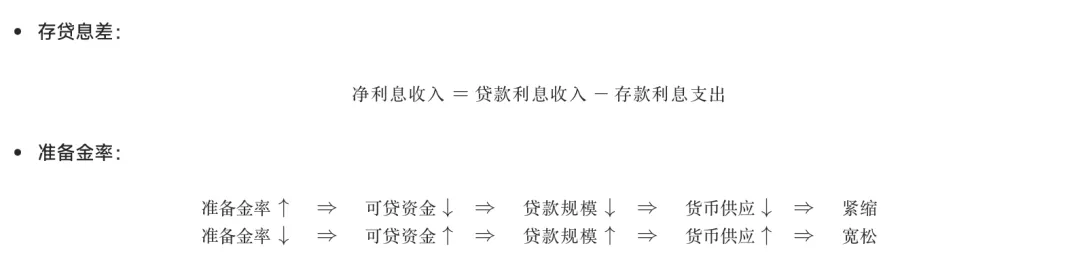

During this evolution, treasuries, as administrative branches, saw their influence wane. However, the central bank–bank system has its flaws: banks profit from the interest rate spread between deposits and loans, while central banks influence banks through reserve requirements.

Image: The role of interest rate spreads and reserve ratios

Source: @ zuoyeweb3

Of course, this is a simplified and outdated framework.

The simplification omits the money multiplier: banks don’t need 100% reserves to issue loans, enabling leverage. Central banks don’t require full reserves either; instead, they use leverage to adjust the money supply.

Ultimately, users bear the risk. Deposits exceeding reserves lack guaranteed redemption. When neither the central bank nor commercial banks absorb the cost, users become the necessary buffer for money supply and withdrawal.

This model is outdated because banks no longer strictly follow central bank directives. For example, after the Plaza Accord, Japan pioneered QE/QQE (quantitative easing), and with ultra-low or negative rates, banks could no longer profit from spreads and often opted out entirely.

Consequently, central banks began buying assets directly, bypassing commercial banks to inject liquidity. The Fed buys bonds; the Bank of Japan buys equities. This rigidifies the system and undermines the economy’s ability to clear bad assets, leading to Japan’s zombie companies, the US “Too Big to Fail” giants post-2008, and emergency interventions like the 2023 Silicon Valley Bank collapse.

How does this relate to crypto?

The 2008 financial crisis catalyzed Bitcoin’s creation. The 2023 collapse of Silicon Valley Bank triggered a US backlash against CBDCs. In May 2024, House Republicans unanimously voted against CBDC development, instead supporting private stablecoins.

This logic is nuanced. One might expect that after the collapse of a crypto-friendly bank and the USDC depegging, the US would embrace CBDCs. In reality, the Fed’s approach to dollar stablecoins or CBDCs is at odds with Treasury- and Congress-backed Treasury stablecoins.

The Fed originated from the post-1907 “free dollar” chaos. After its 1913 founding, it managed a hybrid system of gold reserves and private banks. Gold was under Fed control until 1934, when authority shifted to the Treasury. Until Bretton Woods collapsed, gold remained the dollar’s reserve asset.

After Bretton Woods, the dollar became a credit currency—effectively a Treasury-backed stablecoin—leading to a conflict with the Treasury’s role. To the public, the dollar and Treasuries are two sides of the same coin, but for the Treasury, Treasuries define the dollar’s essence, and the Fed’s private nature interferes with national interests.

In crypto, especially stablecoins, Treasury-backed stablecoins allow administrative branches to bypass the Fed’s currency issuance power. This explains why Congress and the administration jointly oppose CBDC issuance.

Only from this angle can we understand Bitcoin’s appeal to Trump. Family interests are a convenient excuse—the real incentive is the potential for administrative branches to benefit from crypto asset pricing power.

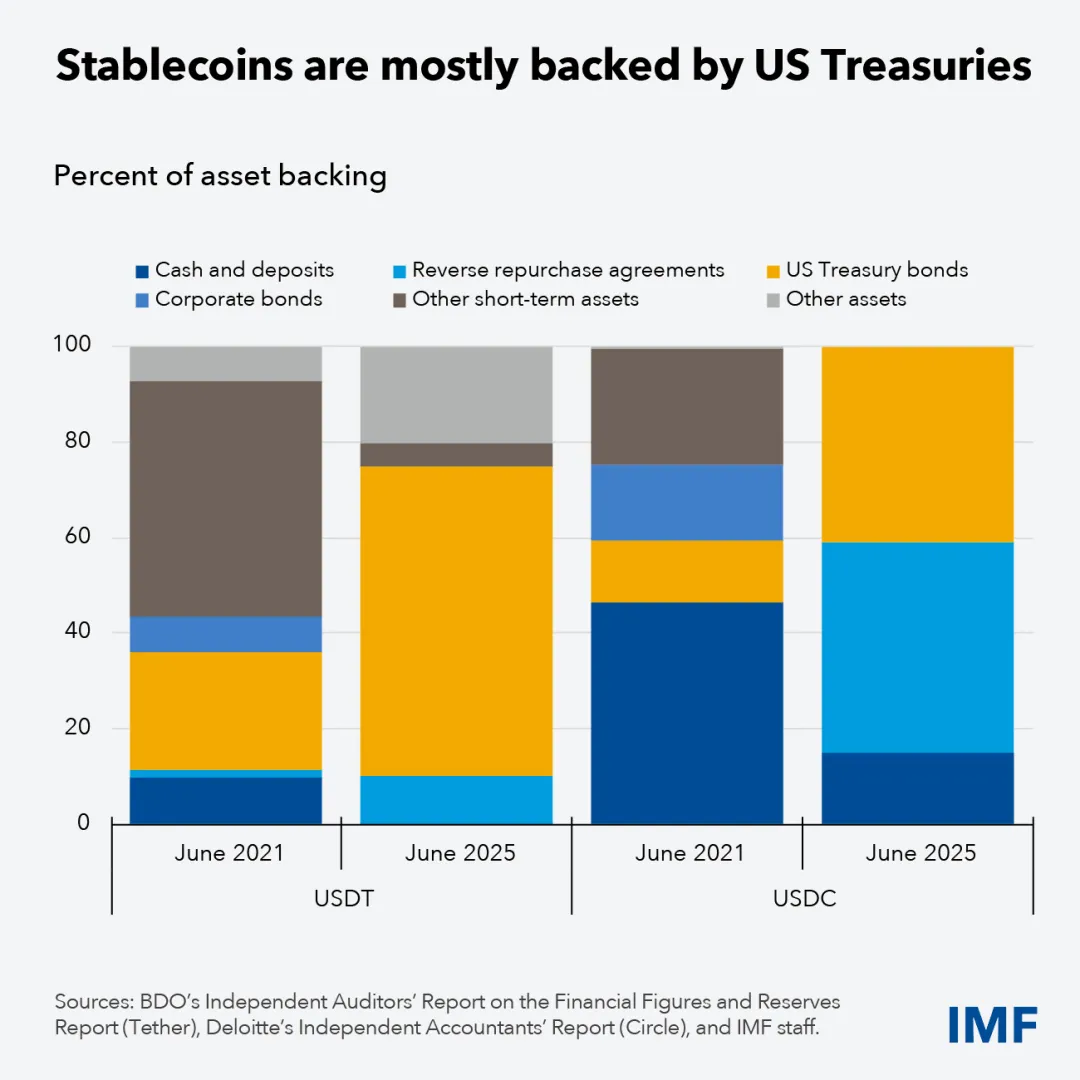

Image: USDT/USDC Reserve Changes

Source: @ IMFNews

Today’s leading USD stablecoins are backed by cash, Treasuries, BTC/ETH, and other yield-bearing bonds. In practice, both USDT and USDC are reducing cash holdings and shifting heavily into Treasuries.

This is not a short-term yield strategy; it reflects a structural shift from dollar stablecoins to Treasury-backed stablecoins. USDT’s internationalization is essentially about buying more gold.

The future stablecoin market will see competition among Treasury-backed, gold-backed, and BTC/ETH-backed stablecoins. There will be no major battle between USD and non-USD stablecoins—no one seriously expects euro stablecoins to become mainstream.

With Treasury-backed stablecoins, the Treasury regains issuance authority. Yet, stablecoins cannot directly replace the banks’ money multiplier or leverage mechanisms.

Banks as DeFi Products

Physics never truly existed, and the commodity nature of money is equally illusory.

After Bretton Woods collapsed, the Fed’s historical mission should have ended, much like the First and Second Banks of the United States. Yet the Fed keeps expanding its mandate to include price stability and financial market oversight.

As discussed, in an inflationary environment, central banks can no longer control money supply through reserve ratios and instead directly purchase asset bundles. This leverage is inefficient and fails to clear out bad assets.

DeFi’s evolution and crises present an alternative: allowing crises is itself a clearing mechanism. This creates a framework where the “invisible hand” (DeFi) governs leverage cycles and the “visible hand” (Treasury-backed stablecoins) provides foundational stability.

Put simply, on-chain assets enhance regulatory oversight as information technology penetrates opacity.

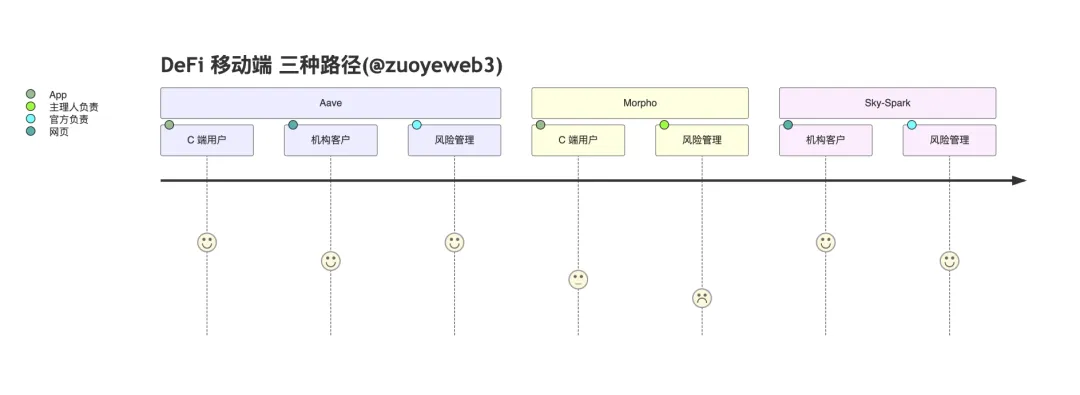

In practice, Aave has built its own retail app for direct user access. Morpho leverages Coinbase in a B2B2C model. The Sky ecosystem’s Spark forgoes mobile, focusing solely on institutional clients.

Their approaches differ: Aave serves both retail and institutional clients (Horizon) with official risk management; Morpho delegates risk to lead managers and outsources the front end to Coinbase; Spark is a Sky sub-DAO, forked from Aave, targeting institutions and on-chain markets to avoid direct competition with Aave.

Sky stands out as an on-chain stablecoin issuer (DAI→USDS), aiming to broaden its use cases. Unlike Aave and Morpho, pure lending protocols must remain open to attract diverse assets, making Aave’s GHO less promising.

Sky must strike a balance between USDS adoption and lending openness.

After Aave rejected USDS as a reserve asset, it was surprising to see Sky’s own Spark also offering limited support for USDS, while actively embracing PayPal’s PYUSD.

While Sky aims to balance both via different sub-DAOs, this inherent tension between stablecoin issuance and open lending will persist throughout its evolution.

In contrast, Ethena took a decisive approach: partnering with Hyperliquid’s Based product to promote HYPE/USDe spot trading pairs and rebates, fully embracing the Hyperliquid ecosystem and focusing on single stablecoin issuance rather than building its own ecosystem or chain.

Currently, Aave is closest to a comprehensive DeFi app with quasi-banking capabilities. It leads with wealth management and yield, directly engaging retail users and aiming to migrate mainstream traditional clients on-chain using its brand and risk management expertise. Morpho seeks to emulate the USDC model, leveraging Coinbase to amplify its intermediary role and deepen cooperation between lead manager vaults and Coinbase.

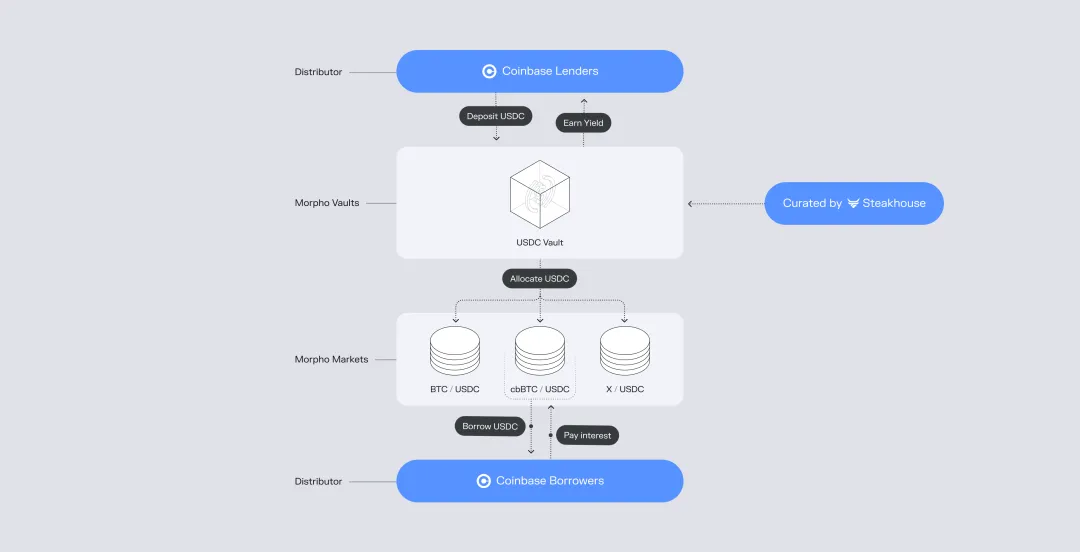

Image: Morpho and Coinbase partnership model

Source: @ Morpho

Morpho exemplifies radical openness: USDC + Morpho + Base → Coinbase. Beneath $1 billion in loans lies the ambition to challenge USDT through yield products and counter USDe/USDS. Coinbase remains the biggest USDC beneficiary.

How does this connect to Treasury-backed stablecoins?

For the first time, the entire process of on-chain stablecoin yields and off-chain user acquisition circumvents banks as central intermediaries. Banks aren’t obsolete, but their role is increasingly limited to on/off-ramp middleware. On-chain DeFi can’t solve the credit system, and challenges remain in overcollateralization efficiency and lead manager vault risk management.

However, permissionless DeFi stacks do enable leverage cycles, and lead manager vault failures can serve as market-clearing events.

In the traditional central bank–bank system, third- and fourth-party payment providers or dominant banks could trigger secondary settlements, undermining central bank oversight and distorting economic signals.

In the modern “stablecoin–lending protocol” framework, regardless of loan recycling frequency or vault risk, everything can be quantified and scrutinized. The key is to avoid introducing unnecessary trust assumptions, such as off-chain negotiations or legal interventions, which would only reduce capital efficiency.

In essence, DeFi will not surpass banks through regulatory arbitrage, but through superior capital efficiency.

For the first time in over a century of central bank monetary issuance, the Treasury is reconsidering its leadership role, free from gold constraints. DeFi is poised to take on new responsibilities in currency reissuance and asset clearing.

The old M0/M1/M2 distinctions will fade, replaced by a binary split between Treasury-backed stablecoins and DeFi utilization rates.

Conclusion

Crypto extends its greetings to all friends. May they witness a spectacular bull market after enduring the long crypto winter—while the impatient banking sector bows out first.

The Federal Reserve is working to establish Skinny Master Accounts for stablecoin issuers, and the OCC is trying to assuage banks’ concerns about stablecoins siphoning deposits. These moves reflect both industry anxiety and regulatory self-preservation.

Imagine the most extreme scenario: if 100% of US Treasuries were tokenized as stablecoins, if all Treasury stablecoin yields went to users, and if all those yields were reinvested into Treasuries—would MMT become reality, or collapse?

Perhaps this is the meaning crypto brings. In an era dominated by AI, we need to follow Satoshi’s footsteps and rethink economics, exploring the true significance of cryptocurrency, rather than simply playing along with Vitalik’s experiments.

Disclaimer:

- This article is republished from [Zuoye Crooked-Neck Tree], with copyright belonging to the original author [Zuoye Crooked-Neck Tree]. If you have concerns about this republication, please contact the Gate Learn team for prompt handling according to established procedures.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions are translated by the Gate Learn team. Do not copy, distribute, or plagiarize this translation without referencing Gate.

Related Articles

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline

Solana Need L2s And Appchains?

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

Navigating the Zero Knowledge Landscape

What is Tronscan and How Can You Use it in 2025?